In late November, I told my husband, “I’m going to an MCG lecture on Tanjore art.”

“Tandoor? Oh, that sounds great! I love tandoori food!” he enthusiastically replied.

His misunderstanding was not intentional. Many great and memorable things originate from India, food and art are just two. While Tandoori chicken and naan are delicious, Tanjore painting is an inedible art form.

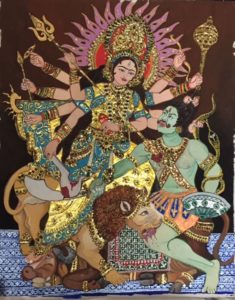

Tanjore painting is a classical South Indian art form originating around the 16th century in Tamil Nadu. It’s embossed texture, rich multi-media materials and vibrant colors distinguish it from other painting techniques. Embellishments include semi-precious stones, glass pieces, and gold leaf. The decadent materials are reflective of the importance of the subject matter, usually a Hindu deity. They were traditionally displayed in kings’ homes or temples. Today, they can be hung as decoration but still have a spiritual purpose in families’ prayer rooms.

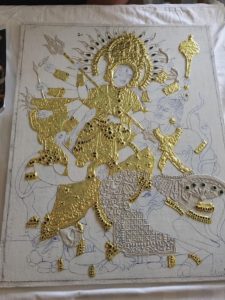

Tanjore paintings are created in several stages, the first: to create the unique canvas. A white muslin cloth is pasted onto plywood, which offers a sturdy base for the upcoming layering of materials. White glue or Arabic gum and water form a muck paste that is piped (think cake decorating) over the composition creating a relief or embossed texture. Into the wet embossing, colorful stones are inlaid. When funded by a wealthy patron, diamonds, rubies, and gemstones were used to decorate the painting, however, semi-precious or plastic stones are also acceptable and fit in a budget. The gemstones adorn the Hindu deities and decorate architectural details. Then real gold foil is applied over the embossing, adding to its decadence and richness. The end result is a very heavy work of art. A thick and ornately carved wood frame kept in a place of honor. Tanjore painting technique is meticulous and time consuming. Completing a medium sized piece can take between three to six months to complete and cost several hundred dollars in materials.

Tanjore painting is grounded in a religious and spiritual tradition. They convey a religious meaning rather than accurately depicting objects and figures. Realistic perspective, proportions and color are less important than the symbolism and spiritual meaning they hold. Notably, the eyes are large, exaggerated and directly confront the gaze of the viewer. The deities are represented by a color unique to their attributes. For example, Krishna and Vishnu are blue, Shiva white. The chosen deity is at the center of the composition, larger than the other figures, and is framed by a curtain or architectural detail. Another trademark of Tanjore painting is a dark blue or black background that accentuates the drama against the gleaming gold and gemstones. Iconography plays an important role with symbols scattered across the piece that are relevant to the God: butter, cows, peacock feathers; are all meaningful symbols.

Religious subjects and rich materials are not exclusive to Tanjore painting. There are similarities to other religious art. In the Byzantine and Orthodox Christian traditions, paintings of Christ, Mary, and the saints: the religious figure dominates the center of the composition. They gaze at the viewer with large unflinching eyes. Gold foil, typically in a halo, frames the face and emphasizes the importance of the face and gaze. In both Tanjore and Byzantine Orthodox paintings, the gaze directly meets the viewer with intention. These paintings were intended to assist in prayer/meditation.

They were objects for the devotee to make eye contact, suggesting familiarity and relationship with the holy figure.

Our hosts Debjani Lahiri and Preeti Sharat invited a small group from the MCG to see a demonstration of the Tanjore painting technique and learn about its origins. Both women know from their own expat experiences the value of learning about other cultures abroad. Debjani recalls since being married, “I have moved 13 times, lived in four countries and lived in approximately 20 houses in the last 24 years.” She is a self taught artist and while living in China, learned Chinese watercolor and ink painting. Although Indian, she learned Tanjore painting only after moving to Malaysia. “My move to Malaysia has proved to be the most exciting and fulfilling move. I picked up Tanjore Painting here and it has turned into a passion.”

Preeti Sharat’s background is equally diverse boasting 25 years as an expat spouse and having lived on four continents in 10 cities. She remembers, “As a girl growing up in a typical Indian family, my pursuits were anything but typical. I did not display the slightest inclination for pursuits like classical dance or singing and even cooking. I stumbled into the world of Tanjore painting in high school as it gave me the opportunity to express myself in any way I thought fit, without being buttoned down by stereotypes.” Preeti is an accomplished Tanjore painter and credits her skill with having studied under a master painter in India when she was a teenager. Since then, painting has been a “constant companion” on her journeys.

Both women believe “painting cuts across all cultures and religions”. We from the MCG small group are truly grateful for the opportunity to understand and appreciate Tanjore painting through them.

Written by Laura Roy