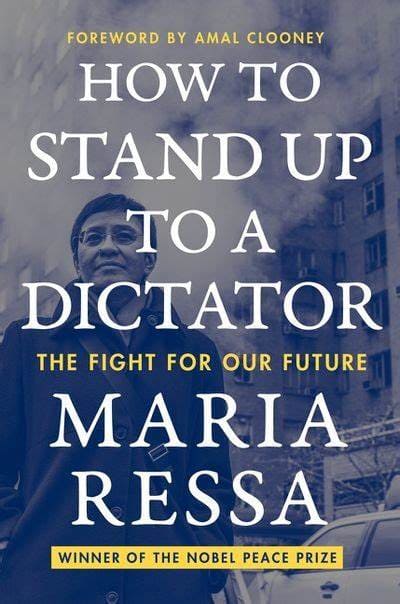

Book Group 1 read Maria Ressa’s How to Stand up to a Dictator on the 31st of May. Some of us had never heard of her before while others among us remember her as a CNN news reader seen here in Malaysia years ago. No matter from where we started, we all have new found respect for Ressa now. The book is an autobiography; outlining her life, which we found most appealing and her career in journalism, some of which was rather technical.

Her childhood was turbulent. Her father died in a car accident when she was one. Her mother, as a single parent, left her children in the Philippines, moved to the States, but then came back to the Philippines and “kidnapped” her daughters, taking them to the States to live with their new step-father. So, Maria grew up in the States from the age of eight in 1973 until she graduated from Princeton in 1986.

On her graduation she decided to return to the Philippines in search of home. At Princeton she had completed the first two years of pre-med, but then became enamored with theatre arts. When she returned to the Philippines she was working on her thesis play, which she was producing for her Fulbright scholarship, exploring the role of political theatre in political change.

A visit with an old friend led her to a job in journalism with PTV4, a private Filipino television station. Her job was to write, edit, supervise, direct and produce a daily live newscast. And so, she was on her way as a journalist. Eventually she became involved with a then young TV network, CNN, who were looking for a reporter in Manila. By 1994, she headed up a new news bureau that CNN opened in Jakarta. During this time journalists and the media were still seen as gatekeepers for public trust and truth and felt legally accountable for everything they published and broadcast. But that didn’t last.

In 2005 she joined ABS-CBN, a Filipino private TV network where she was challenged to make it a world-class news organization. She experienced resistance from the corporate core of ABS-CBN to the changes she wanted to undertake. Feeling frustrated when asked to do something she couldn’t accept, she quit her position. She and three other fellow female journalists decided to create a news website named Rappler in 2011. They became very successful with their video-first focus before Facebook and YouTube employed that approach. They also embarked on many experiments of specific interest and benefit to the Filipino people, such as anti-corruption initiatives. The emphasis was always on reporting the truth.

In a 2011 cooperative, Rappler started posting their experiments on FaceBook and the founders were excited and optimistic about what FB could do for the Philippines. What Rappler didn’t count on was the FB emphasis on promoting their own business model, being co-opted by the state, the scarcity of facts covered, the rise of digital authoritarians and the mass manipulation that became current. Initially Ressa was excited, “We’re more engaged. We’re more social. We can decide to … act together.” She later became totally disillusioned with FB and Mark Zuckerberg.

In the 2016 election, Rodrigo Duterte emerged successful, the first politician to use FB to win a presidential election. During an interview with Duterte in the late 1980s, he made a very prescient promise, if he ever won as president, he would, “… stop corruption, stop criminality and fix government. … When I said I’ll stop criminality, I’ll stop criminality. If I have to kill you, I’ll kill you. Personally.” And so began his reign and his use of the net to spread pro-Duterte disinformation.

Ressa’s continued insistence on reporting the truth, to ‘#HoldTheLine’ to defend the country’s Constitution, set her on a collision course with Duterte. Her increasing international recognition was antagonizing Duterte. As she points out, Nelson Mandela said, ‘For to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.’ The ultimate international recognition, being awarded the 2021 Nobel Peace Prize (along with Dmitry Muratov of Russia for their fight for the freedom of expression), stands against Maria’s 10 arrest warrants on trumped up charges issued by Duterte and the Government’s attempt to silence Ressa and shut down Rassler. Now that he is no longer in power, many of the charges are being withdrawn.

A fellow journalist said of Ressa and Rappler, “We will continue to tell the truth and report what we see and hear. We are first and foremost journalists. We are truthtellers.” Maria herself says, “… as I stood up to the most powerful officials attacking us, people asked me how I found the courage. ‘It’s easy,’ I would often reply. ‘I have the facts.’”

It wasn’t an easy book to read, with so many tech details and some degree of repetition, but we are glad that we stuck with it. We have come away with a new found realization of the dangers of the information crisis of this digital age, about which many of us were unaware.

Leslie Muri