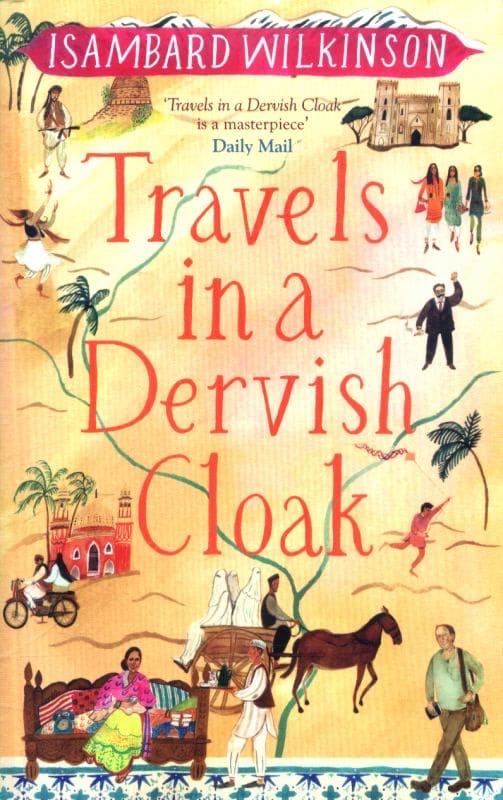

BG 1, March Book Review Travels in a Dervish Cloak by Isambard Wilkinson

Travels in a Dervish Cloak is not strictly a travel book per se. The “dervish cloak” of the title is Pakistan itself—a fraying patchwork garment, in a phrase borrowed from Lahore’s patron saint, Data Ganj Bakhsh. The “travels”, meanwhile, are less a single journey than a series of short trips from Islamabad, made during the author’s time as a correspondent there between 2006 and 2009.

This was a turbulent period for Pakistan, encompassing the final years of Pervez Musharraf’s presidency, the lawyers’ protests which helped bring about its end, the bloody siege of the Islamist Lal Masjid in the capital, and the assassination of Benazir Bhutto. These events all feature in the book, but they are secondary to what Wilkinson suggests was his true purpose in going to the country: a quest for “the essence, the quiddity of Pakistan, which I hoped to find by encountering its mystics, tribal chiefs and feudal lords.”

For Wilkinson, Pakistan was not simply a professional posting. His relationship with the country was already an old one, forged via his grandmother, scion of a Raj-era Anglo-Indian family, and her lifelong friendship with a formidable Pakistani woman, Sajida Ali Khan, known simply as “the Begum”. This personal connection had led to a first teenaged visit to Lahore—“a place of enchantment”—to which Wilkinson returned as a journalist with a sense of nostalgia and spirit for discovery.

As much a political book, there is a first-hand account of the aftermath of the deadly bomb attack on Benazir Bhutto’s homecoming parade through Karachi in 2007; a thoroughly intrepid trip across the lines to meet the rebel Baluch chieftain Nawab Bugti (later killed during a clash with the Pakistan military); and hair-raising forays into the fringes of Taliban territory. The book provided a strong sense of place through description of landscape and atmosphere, whether in the high mountains of Chitral, or in the softer countryside around Islamabad. Wilkinson is particularly adept at catching the hectic scenes during festivals or on city streets, as in his glimpse into the flow of the Lahore traffic. He does have a fascination with the many religious traditions of South Asia, especially in Pakistan’s threatened Sufi places of worship—“epicentres, pulses of Old Pakistan” as he calls them.

Unfortunately a dated book in terms of current references to Pakistan’s political landscape. Nonetheless an enjoyable read.

Nazi Morad