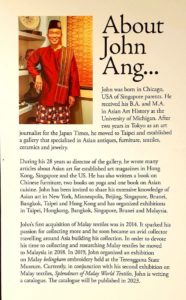

The Splendours of Malay World Textiles exhibition was indeed splendid! The MCG Events Planning Team organized a guided tour for 20 fortunate members on August 17th at Menara KEN in Taman Tun Dr. Ismail. We were treated to a display of 650 amazing pieces from the collection of John Ang which consists of 4000 pieces. Two groups were guided through the exhibition, one led by John and one by a docent, Azman Ahmad.

John, an American of Singaporean parents, has only been collecting Malay pieces since 2014, and his passion for acquiring textiles has taken him throughout the Malay-archipelago in his search for more and more unique pieces. Since 2018 he has resided in Malaysia to facilitate collecting and researching Malay textiles.

John says, “I first started collecting Malay textiles in 2014 and was immediately enamoured by their beauty and complexities. It sparked my passion and I became an avid collector, travelling all over Asia to acquire pieces to add to my growing collection.”

For a novice in the field of textiles, I found the intricate details of the distinguishing features of fabrics and methods of production and purposes head spinning. For me, order was imposed on the bewildering host of innumerable facts by a list of 12 categories and definitions, which informed the exhibition, so I will use that as a guiding structure. The introductory display features examples of singep, pieces of cloth used at the cukur jambul, hair cutting ceremony held on a Malay baby’s 40th day, to bring blessings of health and wisdom to the new born. The display illustrates eight of the 12 types of fabrics listed.

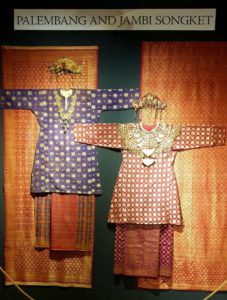

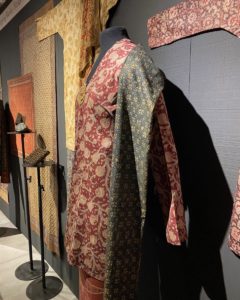

Songket – supplementary gold or coloured weft (crosswise threads) decoration – Decorative patterning created by weaving additional weft threads of gold, silver or various colours above a base cloth. Initially, it was influenced by Indian gold and silver brocades (fabrics woven with raised patterns) but later various regional styles developed throughout the Malay world.

Traditionally known as the king of Malay textiles, songket was worn at weddings and important events and has always been associated with royalty. Songket examples from Palembang, south Sumatra are considered full, as they have a dense use of gold threads, whereas those from the Peninsular Malaysia appear more subtle. Another difference is that the pieces from the Palembang area usually have a finely stitched seam running the length of the sarong, as they were made with a backstrap loom, which limited the width of the cloth while those from the peninsula were made on looms, which allowed for much wider cloth. Silk yarns were used for women’s pieces while those for men were usually a blend of silk and cotton. A common design feature is repeated arrangement of narrow triangles or broad parallelograms running the width of the sarong which appear to be vertical when it is worn, known as pucuk rebung, bamboo shoots.

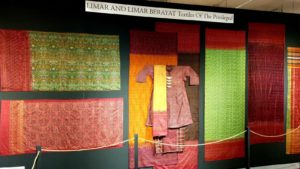

Limar – weft ikat (fabric threads are tied and dyed before weaving)

Fine weft ikat creating by tie-dyeing only the weft threads before weaving. This form of weaving is found in the Cham regions of Vietnam and Cambodia, in South Thailand and the East Coast of the Malay Peninsula as well as South and West Sumatra.

The pucuk rebung pattern on a sarong, can send signals to the community when worn by a woman. Frequently referred to as the muka (face) or kepala (head), the arrangement of triangles worn running down the front signifies a single woman, worn at the back means the wearer is married, to the left or right denotes a divorcée or a widow. Sometimes calligraphy known as bersurat is shown on limar cloth; biasa is normal writing and berayat denotes verses from the Koran.

Telepuk/Prada – gold leaf application cloth

Telepuk – Malaysia, Prada – Indonesia

Telepuk of the Malay Peninsula uses gold leaf that is adhered with gum Arabic and Prada uses glue from powdered fish bone. Later imitations use a powdered gold solution that is painted directly onto the cloth.

Telepuk was probably influenced by Indian fabric varak, where gold leaf is adhered to cloth by stamping patterns with glue onto cloth. Producing telepuk designs involves many steps which may account for the fact that it was worn by royalty. First the cloth is starched, then dried, then layered with beeswax and calendared, when it is rubbed with the back of a cowrie shell to make it shiny. The last step is the printing which starts with applying liquified gum Arabic to the inside of the forearm of the craftsman, the body heat keeping it liquified. Next a carved stamp is touched to the gum on the arm, then to the gold foil and finally to the prepared cloth. Once the gold has adhered, the fabric is burnished once more.

Tekatan/Sulaman – embroidery

Tekatan – Malaysia, sulama – Indonesia

Encompasses various types of embroidery such as tekat suji, tekat, gubah, tekad tinih i, tekat timbul, tekat gem, tekat pekapu, tekat kelingkam, tekat perada mas, tekat rantai, tekat kristik, angkinan, tekat manik manik, tekat labuci and sulaman tabur emas.

There are 16 sub-types of tekat that have been identified. But the basic process is followed: a pattern is cut out then pasted on the fabric. Then the embroidery was done to cover the template in gold, silver or coloured threads. The resulting decorated fabric was especially used by royalty and wealthy Malays. These fabrics were also used to decorate pelamin, the platform where a Malay bride and groom sit during the wedding ceremony. Sequins were sometimes sewn on to add another layer of richness. Strong influences of the Chinese culture are also reflected in the use of tekat displays. Nowadays tekat frequently is used to decorate tudong saji, the wide, low cone shaped food cover.

Pelangi – (Tritik/Jumputan & Sasirangan) – tie-dye

Tie-dye and stitch resist dye. This type of fabric is mostly found in Cham Cambodia and Vietnam, South Thailand, Kelantan and Terengganu, South Sumatra, Pontianak, Mempawah, Ketapang, Banjarmasin and South Philippines.

This form of dying originally comes from India, where it is prevalent. Pelangi-batik combines both tie-dye and wax resist techniques. It is frequently characterized by a rectangular centre which is unadorned and may carry names such as widows’ lives. Waxy banana leaves were sewn on, to prevent dying. Others have centres filled with lozenge shapes. Frequently done on silk, only two or three colours may be used. Regional variations are common.

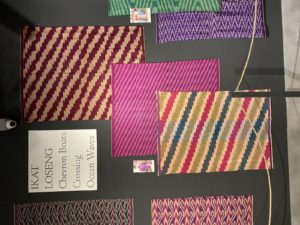

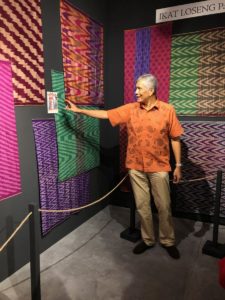

Ikat Loseng – warp ikat (dying of the lengthwise threads)

Warp ikat fabric where the warp threads are tie-dyed first, then arranged on a loom before weaving in the weft threads. They are found most commonly in Sambas and Pontianak in West Kalimantan and also in Kelantan, Pattani and Cham areas in Vietnam.

Two types of ikat loseng are found. In Malaysia we are familiar with the early type made from indigenous cotton, dyed and woven by the Dayak people of East Malaysia, the pua kumbu. After the 17th century silk or cotton examples were produced. Trade with India, the Middle East and Central Asia had influenced and spread this fabric through the Archipelago. Trade through Acheh influenced production through the area. Bands of repeated chevrons often feature in the designs.

Tenunan – weaves of stripes and checks

Plain weaves with check, stripe and other woven patterns. Although Pahang is famous for its numerous check and stripe patterns, other east coast states of the Malay Peninsula, such as Terengganu and Kelantan also produce them in abundance. Makassar, Sumatra and Southern Philippines are also known to produce their own version of checks.

Two of the pieces on display originated from the Palembang regions as can be seen from the fine seam running down the middle. Some showed a chess board pattern, alternating rows of squares of colour. Weaving depicting primarily horizontal or vertical stripes are the common early Malay types, which were frequently done on imported fabrics from as far away as Uzbekistan, India and Syria.

Tapestry – the weave of the eastern periphery of the Malay World

Tapestry – (created by weaving coloured weft thread through plain warp threads, many of which do not run all the way across the warp to allow for several colours and patterns) weave is not common in the western part of the Malay world but it is often encountered in the eastern part, in places such as Manggarai in West Flores, Sumbawa Besar and Bima in Subawa, South Sulawesi, Sabah and South Philippines. Each place has a different name for this weave and so far there is no standardized Malay name for it.

Some of these patterns show large lozenge shapes, and others display rows of repeated diamond shapes. These were woven into square head scarves, long waist cloths and waistbands.

Cetakan – prints, with prints imitating prints

Prints by woodblocks, silkscreen or roller print machine. These printed cloths, mostly made of cotton, were used for clothing. Later when cheaper machine-printed cloths from Manchester and Russia took over the market, they were used more for the lining or backing of more expensive textiles.

Printed fabrics as opposed to intricately woven fabrics have long been found in the archipelago. Initially imported from India, later the Dutch and the English entered the field as it was such a large market. Eventually even the Japanese, Russians and Austrians were involved. Early patterns were carved on woodblocks before machine printing was developed, some later done by silk screen. Patterns reproducing English roses were known as Manchester prints.

Batik – a development from woodblock prints

Patterning by hand or block printing wax resist for the dye. Initially, these were imported from Java but regions/areas such as Jambi, Kelantan and Terengganu began to produce their own style of batiks. In the Malay world, early hand woodblock printed cloths were also referred to as batik even though no was resist was used.

Unlike so many of the fabulous textiles that were the favourites of the royal or wealthy class, batik was worn and used daily by everyone. Batik comes to us from 12th century Java. Originally known as batik tulis, ‘written batik’ the designs were produced by hand using a tool known as a canting, held like a pen, which releases hot wax onto fabric which guided the application of dye. Later copper batik stamps, cap, were introduced to apply the wax resist. Javanese batik makers migrated to the East Coast of the Peninsula and batik cap has been made in Kelantan and Terengganu since the 1920s. Known as batik bersurat, cloth with Jawi or Arabic calligraphy was draped over the bamboo frame used to carry the deceased to the grave. Patterns reflected current events or local tastes, such as a man on a rocket to commemorate Yuri Gagarin’s 1961 space trip or scenes from the Mahabarata in Lombok in the 1890s. Blue and white designs were appreciated by Nyonyas in mouring. A table cloth, drawn with cutlery and plates is even on display.

Renda – lace, dainty elegance from the West

Lace by hand or machine. These were mostly imported from Europe, but later the Malays, especially of Palembang and Melaka became well-known for it. They produce it for clothing, upholstery and table cloths.

Lace had become known and popular during the colonial time. Young students in Melaka and Palembang were taught how to make lace by the missionaries, and these two places became centres of production. Here in Malaysia it was used during the Peranakan time, especially for the cuffs of sleeves. It is frequently used for tudung saji, food covers. Eventually machine-made lace and crocheting supplanted the laborious hand-made variety.

Anyaman – woven mats that adorn the floors of the Malay world

Basketry or matting, woven without a loom with unspun plant fibre such as pandanus, mengkuang or rattan. This type of weaving is found in all regions of the Malay world but those of Sabah, Sarawak, Terengganu and Kelantan are the most sought after.

As Azman said, eyebrows are frequently raised when anyaman is included in a list of textile types. However, as he pointed out, it fits the definition – ‘threads or other materials woven together.’ The fibre needs to be cut, dryed, dyed and then woven. The more narrowly the strips are cut, the finer the design. The most common products are tikar, mats used to cover floors of kampong houses, especially used when eating. Functional items such as baskets and bags are also woven, while mats made with open spaces, which are more decorative.

Never again will I think of the Malay textile world as just songket and batik, now that I have been introduced to such a vast collection of art and fabrics.

The last word is from John, “This collection is my gift to Malaysians, whom I have learned to love since I moved here. I hope it brings you joy and empowers you to be confident of your culture, which has a beautifully rich and diverse history, something worth preserving and celebrating.”

Leslie Muri

Reference: Splendours of Malay World Textiles, www.johnang.com.my